Foreword

The Bernard van Leer Foundation’s involvement in Morocco ran from 1981 to 2008. The story revolves around one key individual – a thought leader and influencer who was the linchpin of our partner in the country as we sought ways to expand and improve preschool education.

The story makes clear the importance of having outstanding partners who understand the local context and the key role of individual leaders in making change for young children. However, it also raises the risk of over-reliance on one individual and the importance of considering the transition to a new generation of leaders as part of our strategy.

The story also illustrates the value of using our funding to help to create a local centre of excellence that – when the opportunity for scale arises – is positioned to contribute. In this case, when the government decided to focus on improving the quality of teacher training, our partner ATFALE had materials ready in the shape of the valise pédagogique, a comprehensive 30-element training system. However, while these teacher training materials scaled effectively, other parts of ATFALE’s model did not. This leads to a second important lesson – that while a comprehensive model may be attractive for a pilot project, opportunities to scale will often require simpler interventions that can more easily be absorbed into existing social services.

I am most grateful to Mr Khaled El Andaloussi from ATFALE for generously hosting the author of this piece, Kay Dilday, and arranging the necessary interviews. We also thank all those involved, and in particular Marc Mataheru, our latest programme officer for Morocco, for his valuable guidance and recollections. At the end of this piece we have added some discussion questions developed from an internal analysis of the case. I hope these and the case itself can trigger useful discussions in other foundations about the role philanthropy can play in achieving greater impact for our youngest citizens.

~ Michael Feigelson, Executive Director, Bernard van Leer Foundation, April 2018

Introduction

Building on Islamic values: A fundamental shift in Moroccan early childhood education

In 2015, the High Council for Education, Training and Scientific Research of Morocco announced its strategic plan for the next 25 years. Among the goals is ‘the institutionalisation and standardisation of preschool education’.

The identification of early childhood education as a national priority for the country represents a tremendous change in the national ethos since 1978, when the Bernard van Leer Foundation first began to support the progress of quality early childhood development in Morocco.

During the nearly 30 years in which it received support from the Foundation, the Alliance de Travail dans la Formation et l’Action pour l’Enfance (ATFALE), the Foundation’s primary partner in the country, succeeded in making quality preschool education a national concern – one recognised as an essential part of the national mandate for education in service of developing a successful, healthy citizenry. It has also succeeded in changing expectations and increasing awareness among parents of the importance of quality early childhood development.

In 1978, when the Bernard van Leer Foundation first entered Morocco, just under 40% of children attended preschool.

In 1978, when the Bernard van Leer Foundation first entered Morocco, just under 40% of children attended preschool, most at Koranic schools focused primarily on a few hours weekly of religious education, with the majority of the children’s time spent in babysitting provided by young untrained women and girls (World Bank/UNESCO Institute for Statistics, online).

Now, approximately 55% of children 4–5 years old attend some form of early childhood education outside of the home (although the percentage is lower in rural areas and greater in the cities). Of these, 81% are in traditional Koranic schools, 10% are in private preschools, and nearly 9% are in preschool programmes sustained by private funding but located in state schools (UNESCO, 2014, online)[1].

1. For further information, please contact: efa2015reviews@unesco.org

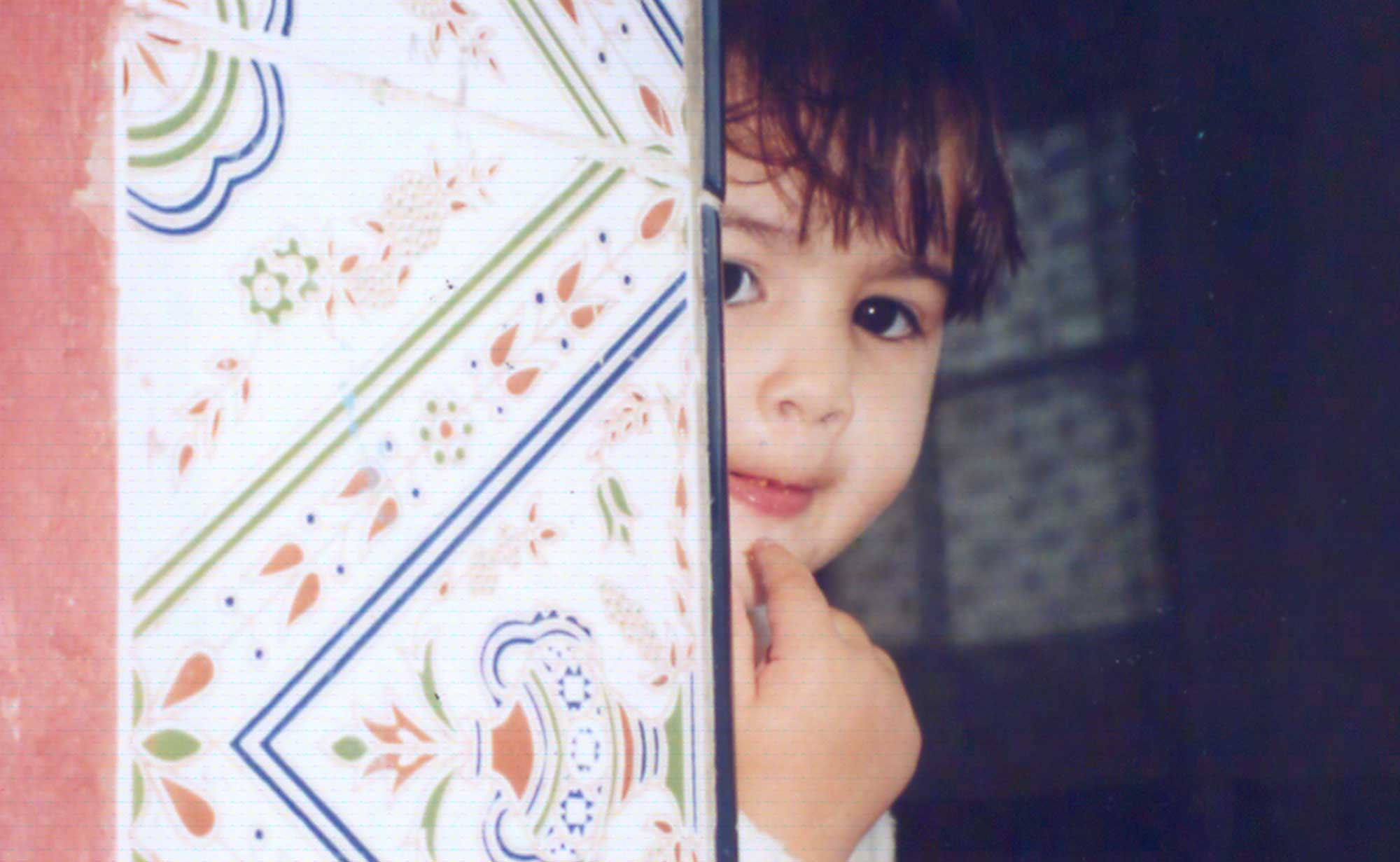

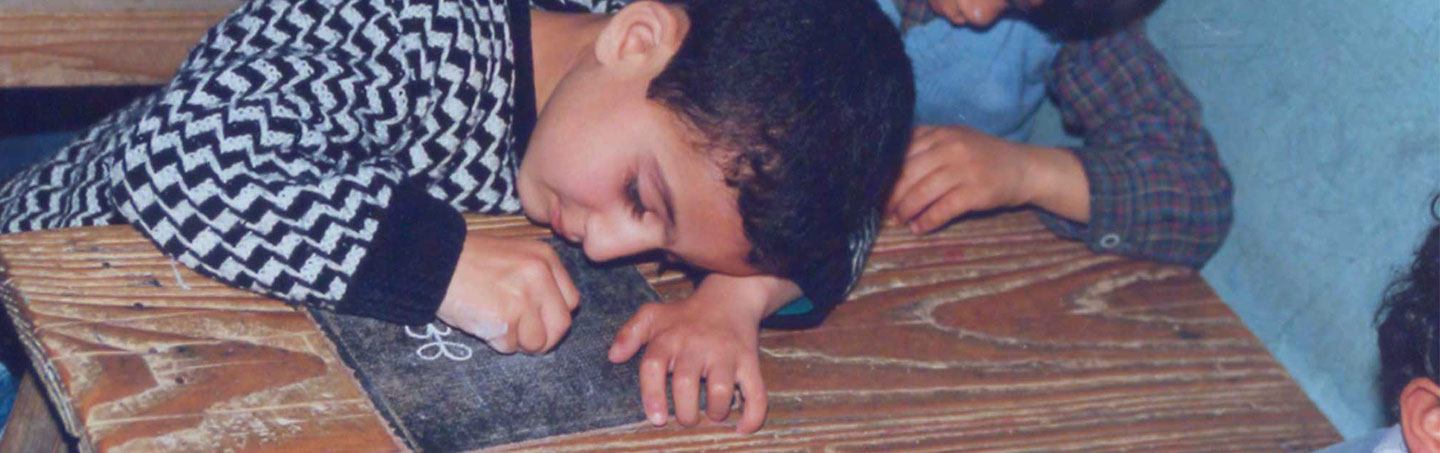

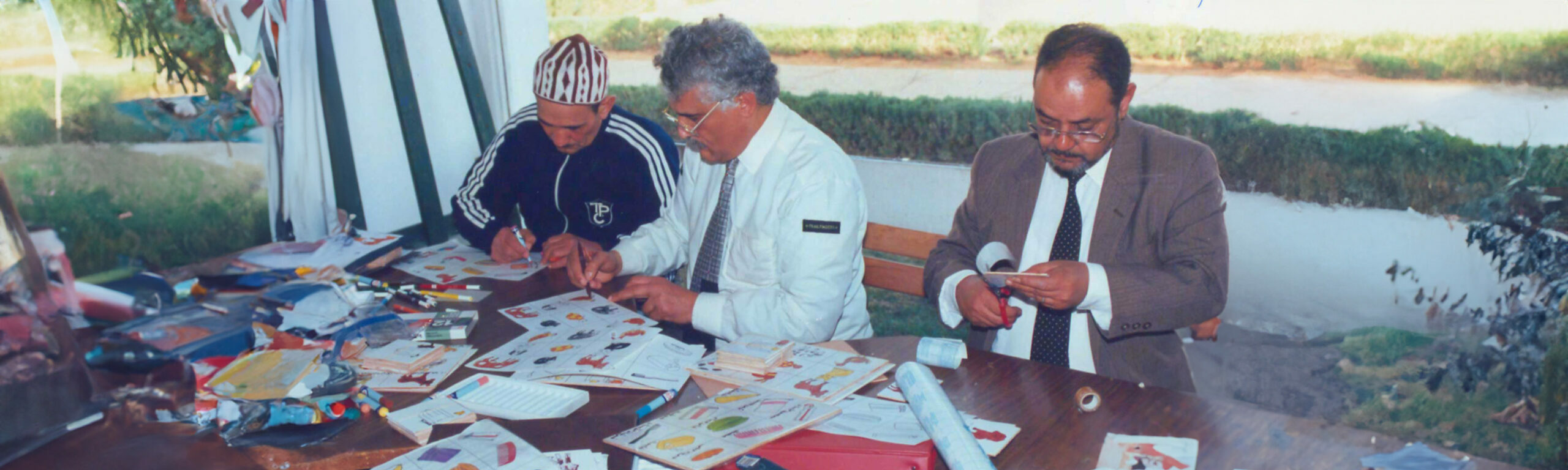

Courtesy: ATFALE

During the first 20 years of the Foundation’s presence in Morocco, several internal government offices were created to oversee preschools. Most of these offices were short-lived or shared oversight with other departments or ministries, creating confusion and complicated oversight. To address this, a number of state agencies collaborated to develop an independent, non-governmental body that would oversee preschool training, in an effort to formalise and universalise modern pedagogy and move away from preschools comprised of untrained staff. Formed in 2008, this agency – the Moroccan Foundation for the Promotion of Preschool Education – is dedicated to providing training in quality early childhood education in partnership with ATFALE.

Supported by the Bernard van Leer Foundation, ATFALE, through in-person training, dissemination of training materials, advocacy and transnational knowledge sharing, has introduced innovations that have been instrumental in transforming both thought and practice about early childhood education in Morocco. To achieve this, over the past 30 years, ATFALE has utilised experts from numerous fields and purposefully worked with all stakeholders: the various government ministries; public, private and religious schools; urban and rural local jurisdictions and families of all income levels.

While there is still progress to be made – most notably in increasing access to holistic, child-centred preschools for children from rural and disadvantaged backgrounds and increasing the number of girls in pre-primary education – much has been achieved during the past 30 years.

“While there is still progress to be made, much has been achieved during the past 30 years.”

The historical place of early childhood education in Morocco

When the Bernard van Leer Foundation first entered Morocco, the nature of early childhood education was not a significant consideration; neither institutionally, as a governmental concern, nor among the private education sector.

The country had emerged from colonisation in 1956, just over two decades earlier, and the government was still struggling with the development of its national educational system [2].

2. In the period following independence until the Foundation entered – the years 1956 to 1977 — Morocco had been through twenty ministers of education (Ibaaquil, 1996; Llorent-Bedmar, 2014).

‘Free’ (that is, state) schools had emerged during colonisation, diminishing the role of the Koranic schools (kuttabs) that had previously educated the majority of Moroccan children from age 7 to 10 (and sometimes even through age 16). As these schools began to lose their students to the free state schools, the kuttabs moved towards accepting young children, age 3–6. Increasingly these young children formed the majority of their student population.

In 1968, the kuttabs’ responsibility for educating preschool students had been made official when King Hassan II charged Koranic schools with the responsibility in a speech. As kuttabs were already taking young children, the significance of Hassan II’s speech was this: he instructed these Koranic schools to perform a role in addition to religious education; the kuttabs, he said, were responsible for preparing children for primary school. He elaborated that this was to be done through a series of activities that introduced children to reading, writing and numeracy; and enabled them to practise sport and activities that used song to teach them the national history of the country. (He then symbolically enrolled his 4-year-old son, the future king, in a kuttab (El Andaloussi, 2005: 29).)

Following Hassan II’s speech, an Office for Preschool Education was created. Beginning in 1975, the preschool sector fell under the division that was in charge of addressing illiteracy. But this division did not survive. Meanwhile, the kuttabs’ role in preschool education had increased to the point where in the 1970s and 1980s, in urban areas, parents often had to prove their children had attended a kuttab for them to be admitted to a primary school (Bouzoubaâ, 1998: 8).

In 1978, UNICEF worked with the Ministry of Education to create a division to transform preschool education by implementing new programmes and by providing ministerial supervision. It was based in the Department of Primary Education, yet few had experience with early childhood education (El Andaloussi, 2005: 36). Despite the deficit of trained personnel, the government was making clear steps indicating that it had, at some level, acknowledged the need for improving the quality of early childhood education. That same year, in 1978, the Bernard van Leer Foundation supported its first programme in the country, working with the Ministry of Social Affairs in a pilot programme to train staff at day care centres in Casablanca, the most populous city in Morocco. At its completion in 1982, the programme had achieved modest success – a small group of workers was trained and the parents involved had gained new ideas about early childhood development and quality education, but it was judged by Foundation staff and national participants as too academic and too local. It was not a project that could be scaled.

The post-1968 shift in the Koranic schools’ responsibilities regarding early childhood education had also created an issue of complicated oversight by government offices. During the period of the French Protectorate, the Ministry of Youth and Sports had been responsible for the preschool sector. This continued during the 1960s and 1970s. As the 1970s drew to a close, the Ministry of Youth and Sports’ authority over all preschool children was increasingly being contested by the Ministry of Education. The Ministry of Religious Affairs also had claim to rights over early childhood due to the Koranic character of the large majority of institutions attended by preschool children, in addition to the cultural importance placed on early religious education (Bouzoubaâ, 1998: 4).

It was at this time, in the early 1980s, that Fred Wood, a programme director with the Bernard van Leer Foundation, approached Khaled El Andaloussi, a native Moroccan who was studying education science at Toulouse-le Mirail University in France. After returning to Morocco in 1983 Mr El Andaloussi became Professor of Education Sciences at the Mohammed V University in Rabat, the capital city of Morocco. The Foundation had been having trouble making an impact in Morocco working directly with the government as its primary partner, in part due to the complicated nature of preschool oversight. Mr El Andaloussi was a Moroccan with both training in and, as Mr. Wood correctly assessed, a passion for creating quality early childhood education in line with the Foundation’s values. A local partner with access to a university department of trained educational experts was well placed to further the Foundation’s mission and create successful liaisons with the government and the educational community.

The number of children in kuttabs had more than doubled between the time of the 1968 royal speech and 1985.

With the support of the Foundation, Mr El Andaloussi and a team of scholars at the Mohammed V University founded the Alliance de Travail dans la Formation et l’Action pour l’Enfance, known as ATFALE, which is both an acronym for the name in French and a word that means ‘child’ in Moroccan Arabic.

The timing was opportune. The situation for young children in Morocco had been changing rapidly. Traditionally, most children had stayed in the home before entering primary school (if they entered primary school at all) and increasingly children were entering kuttabs during their early childhood. The number of children in kuttabs had more than doubled between the time of the 1968 royal speech and 1985.

The steady growth in the number of kuttabs, children served, and teachers at kuttabs during the period following independence:

Yet modern concepts of early childhood education were scarcely visible in the practices. While the royal speech had introduced the notion of institutionalisation and kuttab directors received curricula and textbooks from the Ministry of Education, primarily the kuttabs were serving children in low-income neighbourhoods and the circumstances reflected the poverty of the communities. Classrooms were cramped and often had little access to light or even running water. Teachers were untrained and frequently had received scant education themselves, a situation that was not surprising given the limited access to education for the Moroccan population. It became clear, as ATFALE team member Brigitte El Andaloussi noted, that ‘the ”preschool” concept had to be built’.

In compiling this history of the evolution of early childhood education in Morocco, the Bernard van Leer Foundation asked its staff, Khaled and Brigitte El Andaloussi, and educators, scholars, and government officials involved in the advancement of quality early childhood education in Morocco to reflect on the process over 30 years. They discuss the various steps, gains, setbacks and strategies over the decades, as well as the challenges ahead.

1979 to 1989

The Bernard van Leer Foundation, in partnership with the Ministry of Social Affairs, pilots its first, small programme in Morocco, to train staff who work with young children at day care centres in Casablanca. In 1984, Foundation staff meet Khaled El Andaloussi and begin to support him, and other members of the Department of Education Science at Mohammed V University, in projects that include developing training programmes for early childhood educators in partnership with government agencies.

Khaled El Andaloussi, Founder of the ATFALE team:

I had returned to Morocco in 1983, and the country directors for van Leer contacted me. They had previously financed a project with the Minister of Social Affairs between 1979 and 1983. The project wasn’t going well. I’m not sure why but there were many difficulties. So I was given the opportunity to start a project.

Preschool was limited to replicating a ‘simplified’ preparatory course or just babysitting. It quickly became clear that the ‘preschool’ concept had to be built.

Brigitte El Andaloussi, ATFALE Trainer in Preschool Education and ATFALE Historian:

When Khaled returned to Morocco, he reunited with his colleagues at the university. They created a team of scholars, researchers and professionals who were concerned with early childhood. Their goal was to decide how they could be useful in Morocco after they had returned with their foreign diplomas. At that point the early childhood education sector was completely marginalised. Preschool was limited to replicating a ‘simplified’ preparatory course or just babysitting. It quickly became clear that the ‘preschool’ concept had to be built.

Marc Mataheru, Bernard van Leer Foundation Morocco Programme Officer 2010–14:

In the eighties, the Foundation’s strategy was primarily focused on piloting projects that were innovative in their approaches and would hopefully result over time in the establishing of preschool education services for the most disadvantaged children and families in society.

In doing so, the Foundation had a preference (although not stated very explicitly) to reach agreements with (national) governments and institutions, such as the ministries and associated agencies, to set up ‘model projects’. Projects were funded through a grant to those agencies, with the expectation that these projects would expand over time. The assumption was that, by working with governments, continuity and longer-term sustainability would be ensured when funding by the Foundation would run out.

The Foundation had invested in projects with the ministry in Morocco, but had not seen much progress. Fred Wood had met Khaled in France. He knew the project wasn’t going well in Morocco and told Foundation staff: ‘This is a young man you should meet.’

Courtesy: ATFALE

Khaled:

I sent a proposal to Willem Welling [Executive Director of the Bernard van Leer Foundation, 1968–88] in 1985 to assess or explore the feasibility of the project and that is how it started. I worked with the Ministry of Youth and Sports from 1986 through 1989. The advantage we had was that I was a professor at the Faculty of Science and University Education at Mohamed V and was able to negotiate a project that would be based in the faculty in partnership with the Ministry of Youth. Our objective was to visit preschools in all of the regions that depended on the ministry.

Brigitte:

We tested different forms of on-the-job training with kindergarten managers and their regional managers. Our model consisted of alternating periods of intensive training in Rabat with educators returning to their school for implementation. Participants completed the rotation three times during a school year.

We tested different forms of on-the-job training with kindergarten managers and their regional managers.

Khaled:

Each year we received 20 teachers from different regions. It was more like 30 regions at the time. (At the time we called them delegations and not regions, so 30 delegations.) Subsequently, we worked with the Ministry of Education in training that still continues even now.

Brigitte:

Based on the success of our project with the Ministry of Youth and Sports, a minister from the Ministry of Science and Education visited the Department of Education Science at the university. The function of the Koranic schools had changed over the years. With the development of public education, Koranic schools were left with mostly very young children, children between 3 and 6 years old, as older children went to state schools. In 1990, the Minister of Education asked the faculty to support the preschool kuttabs that were under his jurisdiction.

The 1990s

Supported by the Foundation, ATFALE begins the Koranic Schools Project, a joint effort with the Ministry of Education to address and standardise a level of early childhood education in Koranic schools; the French Government supports ATFALE in training and modernisation efforts in private schools; ATFALE initiates the Groupe Petite Enfance, a monthly meeting for the continuing professional development of early childhood educators in the private sector with meetings nationally. (This group has continued to meet monthly for the past two decades.)

In 1996 ATFALE officially becomes an NGO. For various reasons it is decided that this will enable ATFALE to pursue its work more effectively.

When ATFALE began the Koranic Schools Project, about one-third of all children in the 3–6-year-old age group were in kuttabs, and they constituted about 88% of children in some form or preschool. The remaining children attended modern preschools more similar to a Western model.

At the time, kuttabs in urban areas were generally academically oriented and under the control of the Ministry of Education; rural kuttabs focused more on Koranic education and were generally managed by village communities although the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Religious Affairs had, and still have, a say in their running (Bouzoubaâ, 1998: 4).

Brigitte:

The Koranic schools weren’t used to having such young children. So they put young women and girls in charge of the children and the Fqih [an expert in Islamic law] would stop by to give some Koranic lessons, but the young girls were really in charge [3].

3. In rural areas, the fqih model is the most common. The fqih knows the Koran by heart and has a contract with the community to fulfil a certain number of religious activities, including teaching the Koran to children, in return for being cared for by the community.

Najat El Mdari, Director of Preschool Activities at Al Jisr, an NGO that works to improve the national educational system, and formerly of CARE International:

In some regions, the girls were very, very young, sometimes 14 years old: girls who were untrained academically or intellectually and they would put them in front of children. Often their main goal was just to keep the children from fighting.

Khaled:

Classrooms were designed to accommodate a maximum number of children and most did not have an inner or outer courtyard, which limits the time of recreation or physical activities. Basic equipment was lacking particularly in rural and peri-urban areas (running water, electricity, ventilation, sanitation).

But at this time, Morocco had developed a new vision of the child: Morocco was a signatory to the rights of children; signatory of the Declaration on Human Rights [4]. There was a political atmosphere and an ecosystem that allowed the work we were doing to exist.

4. Morocco ratified the 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child in June 1993.

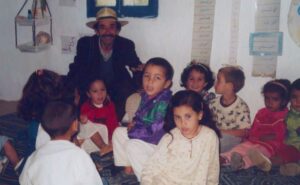

Courtesy: ATFALE

Khaled:

For us, the Koranic Preschools Project was an enormous task: we had to work with the directors of the Koranic preschools, with the ministry, and above all we had to develop a vision that was based on the scientific data on development of the child but also anchored in the social and cultural economic reality of Morocco. We did not talk about ‘preschool’ when we approached the taalim al awali (primary schools): that was our first lesson.

Brigitte:

Working with the Ministry of Education, ATFALE developed a programme of actions to be carried out during the following four years: training of educators and pedagogical advisors, implementation of pilot kuttabs and follow-up in the field.

There was a political atmosphere and an ecosystem that allowed the work we were doing to exist.

The Koranic Schools Project was an extension of the project piloted under the Ministry of Youth and Sports, and had both theoretical and practical ambitions. Its objectives agreed by the Bernard van Leer Foundation and the Ministry were to:

- Develop a child-centred concept of preschool education.

- Support new approaches for the retraining of teachers in the preschool field, aiming to improve their attitudes and skills so as to respect the child’s needs and the socio-economic and cultural environment.

- Develop methods likely to make teachers more sensitive to the necessity of involving all partners in the educational process, particularly parents and communities.

- Develop a training methodology that created a dynamic process for the teacher to integrate innovative and adequate educational practices.

- Stimulate and create more dynamic training facilities in ministries and other organisations involved in the development of young children.

These were all relatively basic convictions that could easily be shared with ATFALE’s partners in the Ministry of Education. The difficulty was to translate these convictions into mutually acceptable practices that would have an impact in the field, and also be acceptable to the religious leaders (Bouzoubaâ, 1998: 10).

The Ministry of Education’s Groupe Koranic Preschool (GKPS) team comprised three primary school inspectors headed by the director of the Primary Education Directorate of the Ministry of Education. After approximately 10 years, ATFALE became independent and continued the work without the involvement of the GKPS.

“We created moments of discussion on the importance of the values … to be passed on to young children by reflecting on the links between the fundamental values … of Islam and universal values.”

Khaled El Andaloussi, ATFALE

Khaled:

The function of the ministry’s advisors was somewhat indefinite. It oscillated between the role of the inspector and the role of the pedagogical adviser. The absence of official status fostered institutional uncertainty and complicated their tasks. All advisers were officials of the Ministry of Education. They were assigned to the various delegations of the country. In 1992, 16 female inspectors joined the advisory cohort to support the actions and contribute to the development of preschool education. Although trained for inspection work in primary education [rather than preschool education], inspectors tried to provide a real effort in the field of preschool education. However, they had to face the resistance of some advisers who were opposed to the changes and the feminisation of the leaders of this sector (El Andaloussi, 2005: 46).

We were able to transform the vision of preschool through our status as academics and early childhood practitioners. The driving force behind this transformation was undoubtedly the introduction of practical activities such as play, motor skills, singing, creative activities … each time highlighting their impact on the learning of young children. This approach allowed us to show the importance of the child’s awakening, his development, his personal development and his sociability. We created moments of discussion on the importance of the values … to be passed on to young children by reflecting on the links between the fundamental values … of Islam and universal values.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT:

During the 1990s, at the Faculty of Education Sciences at Mohammad V, about 20 students each year (from 1995 to 1998) were able to acquire a university education in preschool education. A number of these students were then integrated into the preschool sector in various regional delegations. Their integration in the delegations allowed them to develop a good knowledge of the reality on the ground. Their function was to organise training sessions in resource centres for the benefit of counsellors and educators. We called these delegations advisers, who then had a number of educators to create. We were looking for ‘critical mass’. (El Andaloussi, 2005: 51)

The results as assessed in 1998 by Khadijaa Bouzoubaâ [5], a member of the ATFALE team, were:

New skills, especially in making low-cost learning materials, were acquired, and an estimated 30–70% of the kuttabs introduced manual and artistic activities, psychomotricity, popular tales, work in small groups, excursions and the use of activity corners …

A ‘Mosque Corner’ started to appear in kuttabs. It reproduced the layout of a mosque, featured pictures of Mecca, a prayer mat, the Koran, and the different stages of prayer and ablutions. The latter pictures were important both for the purposes of religious education as well as for acquiring basic knowledge of hygiene and of human physiology …

No kuttab reached by the project shunned the new practices. Some other kuttabs not reached directly by the [Koranic Schools] project even developed their own practices as if to show that they identified with a certain image of modernity. (Bouzoubaâ, 1998)

5. Khadijaa Bouzoubaâ, a researcher at the Faculty of Education Sciences, Mohammed V University, Rabat, had been a part of the ATFALE team since its beginning in 1986.

By the mid-1990s, ATFALE was establishing a reputation in Morocco as a valuable resource for early childhood educators seeking to introduce modern methods of preschool that addressed child development in a holistic way. Other international organisations in Morocco began to utilise ATFALE’s expertise and practical experience, to support the development of this sector.

From 1997 to 2002, the French Government financially supported and worked with ATFALE and the Ministry of Education to open 38 preschool classes integrated into primary schools. It organised training courses for educators and exchanges between French and Moroccan preschool institutions. This project was enabled by the ministerial decision to introduce preschool classes into state-run primary schools. However, despite the involvement of the state in the project, the teachers were paid a salary by private organisations, not by the state. Therefore, while the preschool classes were located in state schools they were funded privately, usually by parents who were financially positioned to do so. (This funding structure continues today and is one of the most significant barriers to the quality education programmes reaching financially disadvantaged children.)

In addition to the work funded by the French Government, ATFALE was approached by the French Institutes in Morocco’s largest cities, and asked to work with private preschool providers.

Brigitte:

In 1995, ATFALE was asked to offer training courses for private preschool institutions by the Instituts Français of Rabat, Casablanca, Méknes, Tangier and Marrakech. The educational poverty of these preschools was equal to that of the kuttabs. But the private sector was the first in Morocco to understand that in order to improve the quality of education, two factors are unavoidable: training and an appropriate salary for educators. In only a few years, it organised itself and offered children a more structured approach.

In the nineties ATFALE also formed the Groupe Petite Enfance which brought together heads of private establishments from different cities in Morocco wishing to improve the quality of their establishments.

Nezha Alaoui, director of a private preschool in a modest neighbourhood of Rabat, member of the Groupe Petite Enfance for 20 years:

I was looking for someone who could guide me and teach me, but also I wanted to really learn to manage and build a preschool worthy of its name. I was introduced to the early childhood group. There were these professors – university professors – and directors of preschools – private schools of course, not from the state schools [in the Groupe Petite Enfance]. We have met monthly for an entire day for 20 years now.

Khaled:

One of the keys to our success has been the adaptation of all our activities to the economic, social and cultural context of Morocco. Beginning in 1997, the Ministry of Education adopted the approach and methodology developed in partnership with ATFALE and decided to try to standardise the experience nationally.

Fouad Chafiqi, Director of Curricula at the Ministry of Education:

It was not conceivable that a foreign preschool concept could be implemented in Morocco. The cement of a society is the school. It is what builds the communal project. The school must contribute to this; the school must have a common foundation for all the children of a society.

Najat El Mdari:

ATFALE found the link between innovation and culture. It has an international outlook: they know what is happening elsewhere, but they are anchored in Moroccan culture. They value Moroccan culture and they have preserved its richness, while they add new educational approaches.

2000 to 2010

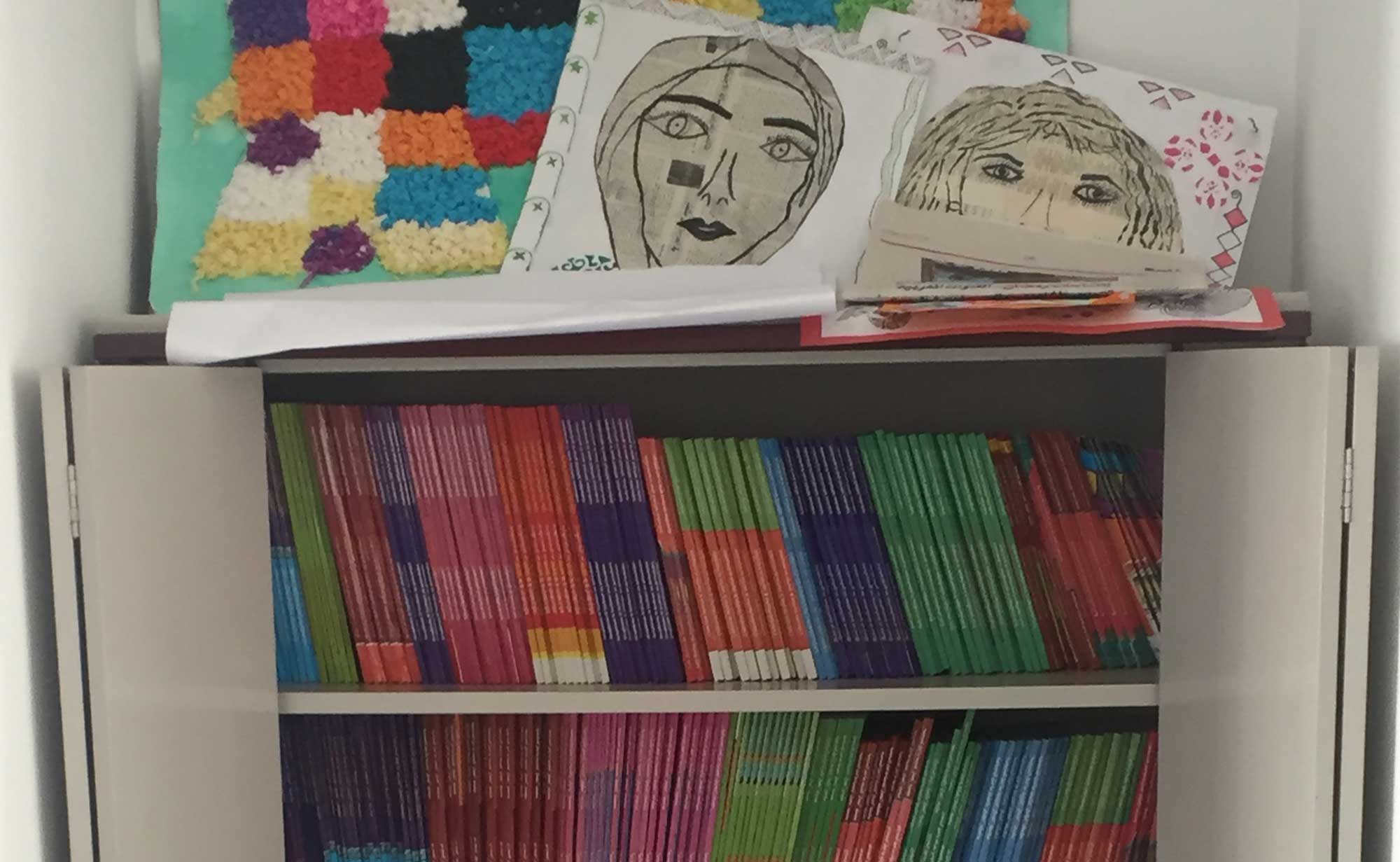

The Moroccan Government introduces a National Charter for Education and Training that identifies early childhood education as the first stage of state-sanctioned education and ATFALE aids in the development of the preschool segment of this charter. Yet the National Charter also detaches preschool education from post-preschool education in the General Private Education Law; ATFALE contributes a monthly column to the magazine Femmes du Maroc, answering reader questions about early childhood education; ATFALE introduces the ‘Valise Pédagogigue’, a comprehensive 30-element training system available as a resource and a self-training tool for those without access to in-person training.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT:

On 23 July 1999, Hassan II died after ruling Morocco for nearly four decades. He was succeeded the same day by his son, Mohamed VI. The 1999 reform of the educational charter was one of Hassan II ‘s numerous modernising projects. In 1999, he also attempted a reform of the Moudawana, the circa 1957–8 Moroccan family laws, in order to end legal polygamy but this did not come to fruition during his lifetime.

In 2004, after a campaign lasting more than 15 years, under Mohamed VI, Parliament passed a reform of the Moudawana. It provided more legal rights for women in all aspects of civic life. Maintenance and education of children was enshrined as a responsibility with no mention of differentiation for the gender of the child. It stated that: ‘Children must be provided with education and training that will enable them to integrate into professional life and become useful citizens in society. To the extent possible, parents must provide adequate circumstances for their children to pursue their studies according to their physical and intellectual capacities.’

In 1999, the government introduced a Charte Nationale pour l’Education et la Formation (National Charter for Education and Training). Education would be a priority for the next ten years and, for the first time, preschool education was officially defined as the first stage of education. The goal was a national standardisation and institutionalisation by 2004, although this was later extended to 2007. (However, as of 2017, they have not yet achieved this goal.)

In 2000, Morocco passed a law entitled ‘The Basic Status of Pre-School Education’, and detached preschool education for 4 and 5 year olds from the General Private Education Law. As part of it, the government officially designated preschool education as the financial responsibility of the private sector.

The law stipulated that the government should establish an incentive system to encourage private agencies (for example, families, communities, NGOs, enterprises and for-profit service providers) to open preschools. It did not specify the types of incentives, which could be tax benefits, subsidies or other forms of support. The government would focus its attention on regulations, training and pedagogical innovations (UNESCO, 2004).

Khaled:

The National Charter for Education and Training was a consensus of many political forces, which was important in 1999 when any attempt at national debate on education resulted in endless debate within Parliament. It was a first step in recognising the existence of the preschool sector (El Andaloussi, 2005).

Brigitte:

Preschool education was recognised as officially part of the school curriculum, with standardisation scheduled for 2004. Faced with this challenge, the ministry encouraged all institutions and civil society to participate in the development effort. This standardisation was not realised for disadvantaged children. The method of financing was the central issue. The low remuneration of educators in disadvantaged preschool sectors prevents them from remaining in the profession. This was a major obstacle to improving the quality of the sector (El Andaloussi, 2007).

Wim Monasso, Bernard van Leer Foundation Programme Officer, Morocco 2002–04:

The absence of minimal organisation in the Early Childhood sector makes preschool education the most representative scene of socio-economic inequalities of the country (Monasso, 2004).

It should be noted that children from the most socially and culturally disadvantaged families are also those who attend the least stimulating and most unhealthy preschool institutions.

Khaled:

The private sector manages almost all of the preschools in Morocco. Even when we say there is a public sector, that means a few classes integrated into the primary schools put at the disposal of an association to manage them. We cannot really call them public since educators are not paid by the public service but by the association. That means by the parents … it is the parents who support this sector.

It should be noted that children from the most socially and culturally disadvantaged families are also those who attend the least stimulating and most unhealthy preschool institutions. The most favoured children receive all the benefits: they benefit from the best preschools, the ones that are most open to modern techniques and the best framed. But this is not more than 8% of preschool children (El Andaloussi, 2005: 36).

Fouad Chafiqi:

There are so-called modern preschools in cities. In some neighbourhoods we have preschools that espouse a much more modern view. They have a vision of a child in all of his needs: psychology, psychomotor and cognitive needs. When these needs come into play and are taken into consideration one can say that it is a preschool that is close to a modern model of preschool.

In a 2004 interview, the Chief of the Section for Early Childhood and Inclusive Education, Division of Basic Education of UNESCO, expressed concern about the Basic Status of Pre-School Education law. Namely, that legally delegating the responsibility for the cost of preschool education in state institutions to parents and the private sector would improve education only for wealthy children. A Ministry of Education representative for Morocco acknowledged this, replying: ‘We are aware of this possibility, but we have not yet devised measures to address it’ (UNESCO, 2004).

In 2007 ATFALE completed a Ministry of Education-endorsed ‘Valise Pédagogique’, born of a desire to target the rural world where the modern style of preschool was almost non-existent, and Koranic schools primarily welcomed only little boys.

Courtesy: Kay Dilday

It was thought that a pedagogical kit that brought together basic elements of holistic early childhood education would enable isolated rural educators to strengthen their practice and create preschools. The pedagogical ‘suitcase’ is composed of 30 elements (educational guides, books for young people, games and teaching tools) for preschool educators, educators and children, and is available in French and Arabic, with some elements also in Tamazight [6]. It was intended as a self-training tool for all preschool personnel who had not been able to access training in the field (El Andaloussi, 2007).

Najat El Mdari:

Morocco has an oral culture but ATFALE has written it down and made the ‘valise pédagogique’. To write it down, that is very rare in Morocco. And this valise pédagogique, which they have made available to all who work in the preschool field, costs zero dirhams [Moroccan currency]. If you want it, you just have to pay for the printing. That is important and that’s new for us. It’s amazing. It shows that they are people of value who are people who are honest and who do not want money.

Morocco has an oral culture but ATFALE has written it down and made the ‘valise pédagogique’… And this valise pédagogique, which they have made available to all who work in the preschool field, costs zero dirhams [Moroccan currency].

6. Tamazight (also called Amazigh) is a language spoken by many of the Berber people of Morocco. In 2011 it became an official language of Morocco (joining Modern Standard Arabic).

In 2008, ATFALE played a role in creating the Fondation Marocaine pour la Promotion de l’enseignement préScolaire (FMPS) [7]. This was a significant step because it was a joint programme involving several Moroccan agencies, and a movement towards bringing all preschool under one umbrella for training and curriculum.

The FMPS evolved from a 2007 study to assess the situation of preschool and learn about the ways to address it and standardise it. The FMPS was established to work on implementing the recommendations of the study to develop a national preschool system.

7. The Ministry of Education, Higher Education, Scientific Research and Professional Training, Ministry of Interior and the Mohammed VI Foundation for the Promotion of Social Works for Education and Training, pooled their efforts to initiate the development of this new national preschool system in partnership with ATFALE. Focused on training, its aim is to universalise access to a preschool education of normed quality.

Fouad Chafiqi:

At that time there was the High Council of Education, headed by the late Abdelaziz Mezian Belfiqh. He wanted to put in place a model of preschool education that could be replicated and standardised. That is why he invested in the FMPS, which is also outside of the Ministry of Education. The FMPS must ensure the quality of its training and ensure that it is of equal quality everywhere. However, FMPS is not the Ministry and has developed its own pedagogical model.

In partnership with ATFALE and the Faculty of Education Sciences, FMPS set up a programme for initial training in preschool education. It involves multidisciplinary trainers: university professors in various fields related to early childhood education, such as child sociology and psychology, preschool practitioners, as well as other stakeholders in medicine, art and management. In 2009, the FMPS started the process of regionalisation of this training. The objective was first and foremost to ensure human resources in sufficient quantity and nationwide.

Abdelhanine Belhaj, Dean of the Faculty of Education at Mohammed V University:

The experience with ATFALE is very valuable. They have the skills required for a good training and people who have a lot of experience who are able to pass on their knowledge and skills to their students. I have found students who were transformed in only one year.

Najat El Mdari:

Of course the [pedagogical] authority on preschool in Morocco is ATFALE. We had developed a strong relationship in 2007 when I worked at Care International, working together on a project that covered a number of themes including preschool. When I came to Al Jisr, I went to find them. The ATFALE method of training is very successful. Educators who have received this training and who apply it in their institutions get extraordinary results.

2010 to 2015

As part of a strategic refocus in 2009, the Bernard van Leer Foundation prepared to exit Morocco. ATFALE, and its concept of quality early childhood education, had become the model in Morocco. However, national standardisation of the model had not been achieved, with rural and disadvantaged areas in particular missed by advancements.

As the Foundation prepared to exit, in partnership with ATFALE, its programme officer for Morocco, Marc Mataheru, assessed that ATFALE had built a solid base over the 22 years it had been supported by the Foundation. This strong base made expanding the preschool education programme in Morocco possible, but it would require additional time and resources to ensure continued scaling and permanence of quality early childhood education in Morocco.

Thus the Foundation and ATFALE worked together to develop an exit strategy. This involved providing funding through 2014 to allow ATFALE time to reinforce its capacity to raise funds and ensure income from other sources, while continuing to invest in its core activities which included:

- training of preschool education teachers;

- development of training materials and specific aspects of the curriculum (e.g. more attention to violence in the classroom);

- lobbying for policies to ensure that the preschool system would become formally anchored in the educational system;

- undertaking the necessary documentation and research activities;

- organising workshops and conferences.

2015 into the future

The challenges that remain in universalising quality early childhood education in Morocco

Khaled:

His Majesty made it clear in the speech of August 12, 2013: national education does not belong to any party. It belongs to the whole society and therefore we must manage education. Politics and education are not the same.

The state must support this educational vision and move in this direction with the opening each year of a number of classrooms. I have calculated for the moment 125 preschool classrooms per year. This is manageable: it’s not the sea to drink. And each year a little increase. By the end of 2029, all Moroccan children would have a preschool place.

Often the obstacle is one of means; to reform the preschool sector will cost a great deal. There would be annual need for training, development, research and creation of structures to accommodate children who have not benefited from preschool – an upgrading of the entire current sector to embrace and adopt this vision. But considering that the state already spends approximately 5% of its GDP on education, the amount needed would not be much more [8].

8. Moroccan newspaper L’Economiste noted that, according to the FMPS, 100 million dirhams would allow them to open very quickly 1,200 additional classes, which would be equivalent to an average of 26,400 children (Nazih, 2016).

Fouad Chafiqi:

Preschool traditionally has no clear educational authority and has no clear infrastructure. Concerning preschool, the authority is not the Ministry of Education’s alone. There is Youth and Sports for crèches; the Habous Ministry over Islamic values – therefore several speakers.

Khaled:

No department has wanted to cede its share: Education; Youth and Sports; National Service.

Fouad Chafiqi:

The relationship between the ministry [of Education] and ATFALE is a special relationship: at face is an autonomous structure that has its own vision. The ministry is an instrument like all the instruments of the state whose mission is to put in place a policy of the state in the field of education. So there are already many things on which there are convergences but there are a number of elements on which there is no convergence between ATFALE and the ministry. It is for that that the ATFALE project was recognised by the Ministry of Education. The ATFALE project has a certain vision of the child. A certain vision of the roles and tasks of the preschool, the types of activities that should be in place in this preschool but also of the inputs and outputs of this preschool – how a child is received and how this child should be when he leaves at age 6. But this [ATFALE project] is not the ministry’s plan.

Abdelhanine Belhaj:

Between ATFALE and the state it is first of all the recognition of the relevance of the preschool. This importance is reflected in the strategic orientations. The state has acknowledged that ATFALE has expertise and experience in the matter. It has also been realised that preschool is a very important step that should not be overlooked. We were not aware of this before. Now the preschool stage is considered by Moroccans as a fundamental step. At the sociological level, all families with children realise that preschool is fundamental to the education of their children. There has been a recognition that we will only have successful quality education with quality preschool. Now we have to set up the mechanism to install it.

ATFALE has very, very deep experience in managing everything that is preschool. They also have skills at the human level in terms of resources for preschool education. It would be really interesting simply to explore the potential that they have. It would be a pity not to take it into account.

“Preschool has always been the poor relation of the education system.”

L’Économiste (Moroccan newspaper), 21 June 2016

Nezha Alaoui:

Really, I’m very grateful for the Groupe Petite Enfance and ATFALE. They are very serious people. They are the people who do the training that founded the norms of Morocco.

Najat El Mdari:

For me they are fighters and they are the people who know exactly the importance of preschools in Morocco.

Khaled:

Quality preschool education should be the norm for everyone. Not just for the private schools that have access to parents who have the means to pay while preschool classes in the countryside have nothing. No, they should be given the logistical and organisational human resources to achieve the same quality. Obviously there are differences that will always exist. But it is that vision that is important for us and that we have worked for at ATFALE. It is for this that the Foundation has supported us for a number of years and it has now become the official vision. For us it is a huge recognition and it is a success.

For nearly 30 years, the Bernard Van Leer Foundation worked with ATFALE as its primary partner in Morocco. While the Foundation often forms partnerships with national governments – as it did during the Foundation’s early years in Morocco – complicated programmatic relations with the government meant that progress was slow to non-existent in the late 1970s through the early 1980s. Thus, those responsible for Morocco operations at the Bernard van Leer Foundation made the decision to support Mr Andaloussi and ATFALE as the Foundation’s primary partner and the primary liaison with the national government.

Support from the Foundation enabled the founding in the mid-1980s of ATFALE as a project of the Faculty of Education Sciences at Mohamed V University. The Bernard van Leer Foundation continued to provide financial and operational support through ATFALE’s establishment as a university-affiliated standalone NGO in 1996, and continuing through the following two decades. During this time ATFALE was increasingly identified as the primary resource and reference for quality early childhood education in Morocco; it worked with (and received funding from) international partners including UNICEF, USAID, Coopération Française and Coopération Belge, as well as working with the national partners referenced previously.

Because of the Foundation’s support, Khaled El Andaloussi and ATFALE held a unique position during three decades, one that provided a consistency that enabled success. While Morocco did not weather 20 Ministers of Education in 20 years as it did in the period immediately following independence, nonetheless, during ATFALE’s existence, education ministers and ministry staff have frequently changed. The financial freedom provided by the Bernard van Leer Foundation permitted ATFALE to negotiate shifting winds in the country and at the Ministry of Education. New relationships constantly had to be built, but because of the stability provided by the Foundation’s support, ATFALE’s survival was not dependent on these relationships.

But, although funding was provided by an international foundation, Mr El Andaloussi and, by extension, ATFALE, were of Morocco, in that he was a university professor and ATFALE originated in an established and respected Moroccan institution, Mohamed V University; ATFALE was well placed to utilise personnel linked with the Rabat-based university as either professors or students. In addition, the ATFALE team drew on the expertise of scholars from a variety of disciplines and people with practical field experience. ATFALE’s survival and success were in part because it worked with all stakeholders: private schools, association-funded state schools and religious programmes, while the Foundation was able to provide ATFALE with the stability to ensure consistent progression and scaling of initiatives.

Over the 30 years, Bernard van Leer Foundation programme officers largely chose to support ATFALE rather than becoming heavily involved in its administration and programme design. In keeping with the Foundation’s focus on developing and sharing knowledge about what works in early childhood development, ATFALE benefited from the Foundation’s links with outside organisations, and was able to organise conferences that brought in international experts to exchange ideas with Morocco’s early childhood educational community.

It has also been realised that preschool is a very important step that should not be overlooked. We were not aware of this before.

This confluence of approaches by the Foundation and its partner, ATFALE, has succeeded in making quality early childhood education a national concern in Morocco. As stated in the oral history by Abdelhanine Belhaj, Dean of the Faculty of Education at Mohammed V University:

It has also been realised that preschool is a very important step that should not be overlooked. We were not aware of this before. Now the preschool stage is considered by Moroccans as a fundamental step.

Over 30 years the Foundation’s involvement in Morocco has helped to dramatically transform thinking about the importance of early childhood education and redefined the perception of quality education. On the state and societal level, it has been recognised that an education that attends to the whole child is a crucial early step, and one that defines the country’s future population.

With dedication, the government will enable this to become a reality for all Moroccan children, regardless of family income or geographical location.

LEARNING QUESTIONS

We commissioned these historical studies in part to identify questions we should ask ourselves as we plan future work. Learning questions raised for us by this story include:

- What factors should we consider in deciding if we should work through a local civil society organisation or directly with the government?

- How can we arrange our engagement so that we are not over-dependent on one individual or institution, but at the same time foster and support local leadership?

- How do we design a pilot so that it is more modular – i.e. easier to scale piece by piece, in the event at this is more realistic? Should we pilot comprehensive models at all?

REFERENCES

Bouzoubaâ, K. (1998). An innovation in Moroccan Koranic preschools. Working Papers in Early Childhood Development. The Hague: Bernard van Leer Foundation.

El Andaloussi, B. (2007). ATFALE ou 20 ans d’engagement dans le préscolaire marocain. Le Furet 53.

El Andaloussi, K. (2005). Développement de l’éducation préscolaire: réalités et perspectives. In: Lamrini, A. (ed.) Systèmes Éducatifs, Savoir, Technologies et Innovation. Rabat: Kingdom of Morocco.

Ibaaquil, L. (1996). L’École Marocaine et la Compétition Sociale: Stratégies, aspirations. Rabat: Babil.

Llorent-Bedmar, V. (2014). Educational reforms in Morocco: evolution and current status. International Education Studies 7:12.

Monasso, W. (2004). Draft Morocco Country Strategy Paper. Bernard van Leer Foundation.

Nazih, A. (2016). Préscolaire: La generalisation dès cette rentrée. L’Economiste 21 June.

UNESCO. (2004). ‘Encourage Private Sector’: Pre-school Education Reform in Morocco, UNESCO Policy Brief on Early Childhood No. 20. Paris: UNESCO. Available at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001374/137409e.pdf (accessed January 2018).

UNESCO. (2014, online). Education for All 2015 National Review: Morocco. Available at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002317/231799e.pdf (accessed January 2018).

World Bank/UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (Online). Gross enrolment ratio, pre-primary, both sexes (%). Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.PRE.ENRR?locations=MA (accessed January 2018).

1980-2015