Vulnerable migrant groups in the Netherlands have higher-than-average rates of pregnancy and birth-related complications and maternal and infant mortality. Centering Pregnancy offers a group care model in which up to 15 Eritrean refugee women meet regularly during pregnancy for medical and psychosocial care, sharing experiences and learning from each other. Under the name Centering Parenting, it continues during the first two years after giving birth.

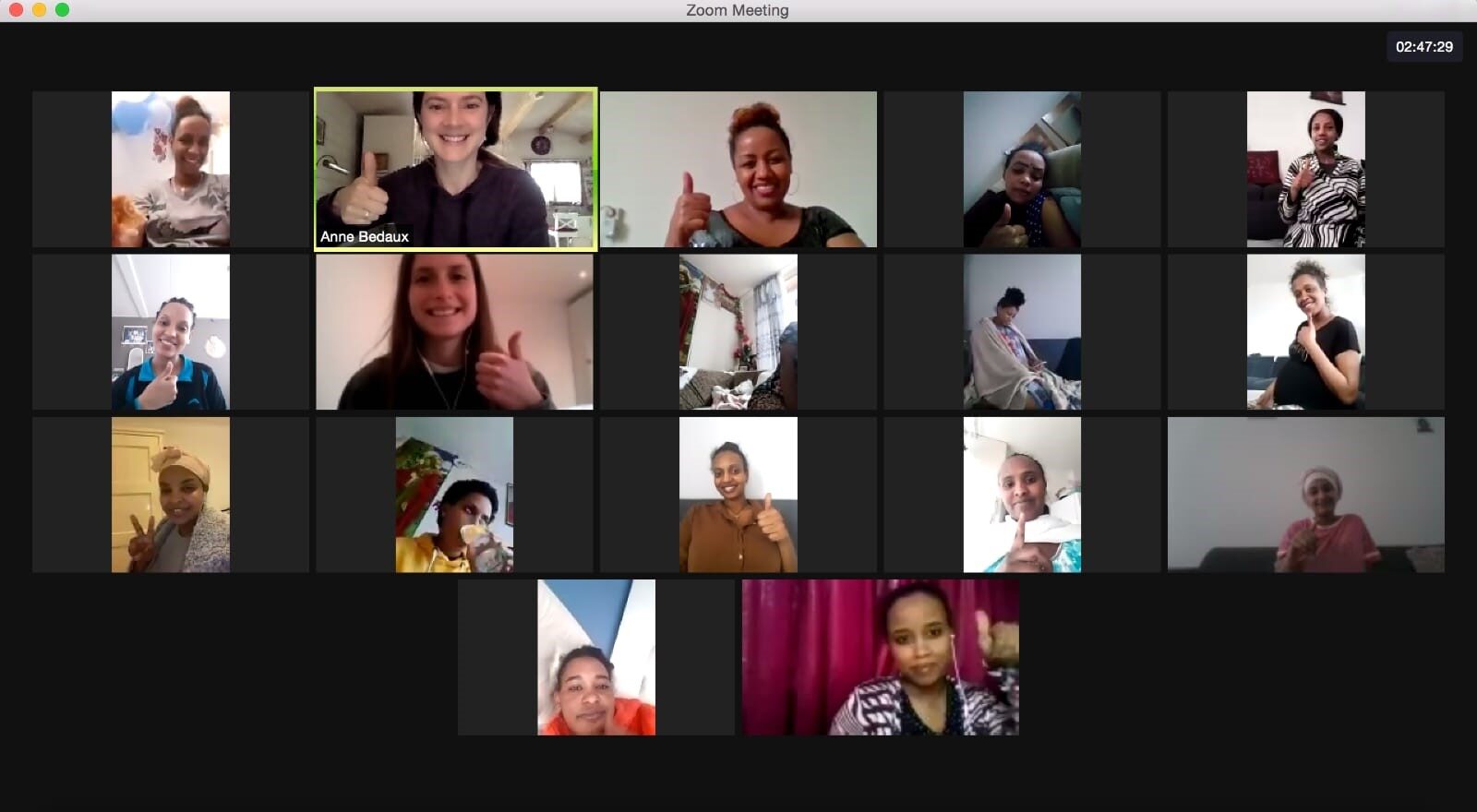

Photo: Courtesy of Caro Bonink

Midwife Anne Bedaux and cultural mediator Amy Welde Selase together set up the programme to provide resources and a network for Amsterdam-based midwives who found they were struggling to overcome language and cultural barriers to provide proper care to pregnant women who had recently arrived as refugees.

“Our goal is that all our participants feel they belong to a safe and familiar network which can help to build up their lives with their newborns in this new country,” explains Anne Bedaux, Centering Pregnancy trainer and supervisor.

One example of the need for a culturally sensitive approach concerns Suwa, a home-brewed beer that almost all the women have been told it is good to drink during pregnancy. Rather than telling the women not to drink it, Anne asks questions such as “‘How are the men after a number of glasses of Suwa? Would there be alcohol in it?’ A dialogue is created and when I ask afterwards if they are still going to drink Suwa, everyone says no.”

Other topics often discussed include contraception, domestic violence, female genital mutilation, the Eritrean custom of removing a baby’s uvula, and the Dutch birth care system – which differs from that in Eritrea, where women who live in rural areas give birth at home with the help of a woman from their village who is experienced but not medically trained.

Expanding across the Netherlands

As the Covid-19 pandemic forced the service online, the initiative found that it was able to reach beyond Amsterdam into other municipalities in the Netherlands. There are 10 online sessions before birth to help parents to prepare, and 15 more sessions after birth for those who continue. The sessions cover topics such as healthy behaviour, choice of delivery method and pain relief during the delivery, caring for a new baby, how to register for services, and building social contacts and support.

As of April 2022, 219 women from 72 municipalities had participated in groups, with many women saying it was easier for them to join online groups than come to in-person meetings as they did not need to travel or arrange for childcare.

The potential for further scale

The model has significant potential to scale further. It could support Eritrean and other women internationally, including in refugee camps. Or it could be adapted to reach other vulnerable migrant groups in the Netherlands: the model is currently being adapted for Ukrainian refugees. The online model easily allows facilitators to show images and videos, and the women to show their homes.

Photo: Courtesy of Caro Bonink

However, not all medical care can be delivered online – some physical care consultations still need to be provided by a nearby midwife, though technology will increasingly expand the scope for self-assessment and remote support. There are now over 75 organisations in the Netherlands who refer Eritrean clients to the service.